Capitalize on today's evolving market dynamics.

With changes to taxes and interest rates, it's a good time to meet with a wealth advisor.

Bond yields offer a stronger opportunity to lock in income, with 10-year U.S. Treasuries holding near a 4.00% -4.25% range.

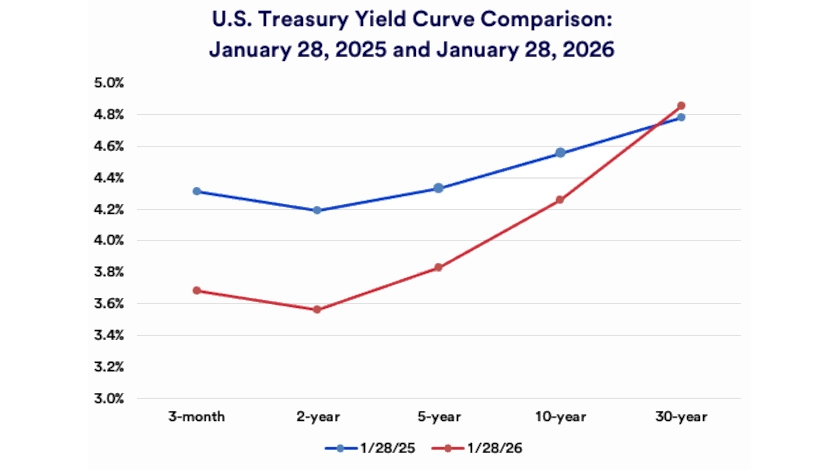

Fed rate cuts in 2024 and 2025 lowered short-term yields, while growth and inflation expectations kept long-term yield rangebound.

Treasury supply and fiscal policy can pressure yields over time; diversified bond portfolios help balance income, risk, and flexibility.

Bonds can strengthen a diversified portfolio, and today’s market gives investors a clearer chance to lock in income than they have had in years. Investors no longer need to rely only on U.S. Treasuries to pursue yield, but moving into other bond market sectors requires accepting different risks and tradeoffs. Since August,10-year Treasury yields have generally stayed in a 4.00 to 4.25% range, while other bond types offer additional yield in exchange for credit, liquidity, or interest rate risk. 1

Rates also move for different reasons depending on their time to maturity, and investors can make better decisions when they separate those forces. Central bank policy and rate expectations typically dominate short-term yields because central banks directly influence overnight financing rates. Longer-term yields respond more to economic growth and inflation expectations, while credit quality shapes the extra yield investors demand outside the Treasury market. The supply of bonds, the amount of money borrowers need through time, influences all bonds.

Many bond investors want dependable income, but they also want flexibility if markets and income opportunities shift. Bonds can help fill that role by blending cash flow potential with diversification, especially when yields offer meaningful compensation for risk. In this environment, bond buyers can look beyond a single fixed income category while still building a disciplined, risk-aware allocation.

“Economic conditions can support continued earnings growth, creating favorable equity and real asset return opportunities.”

Bill Merz, head of capital markets research with U.S. Bank Asset Management Group

Investors also benefit when they frame fixed income decisions around purpose, not prediction. Income needs, time horizon, and risk tolerance matter as much as any single rate forecast because those inputs determine how much volatility a portfolio can absorb. When investors match bond exposures to goals, they can pursue yield more confidently while keeping overall portfolio risk aligned with plan.

“Federal Reserve (Fed) rate cuts pulled short-term bond yields lower,” notes Bill Merz, head of capital markets research with U.S. Bank Asset Management Group. “However, longer-term bond yields remained rangebound in recent months due to lower inflation expectations offsetting stronger economic growth expectations.” The markets watch those crosscurrents closely because they help explain the divergence between lower short rates and stable longer rates Investors can use that same framework—policy on the front end, growth and inflation further out—to interpret why different behavior across maturities.

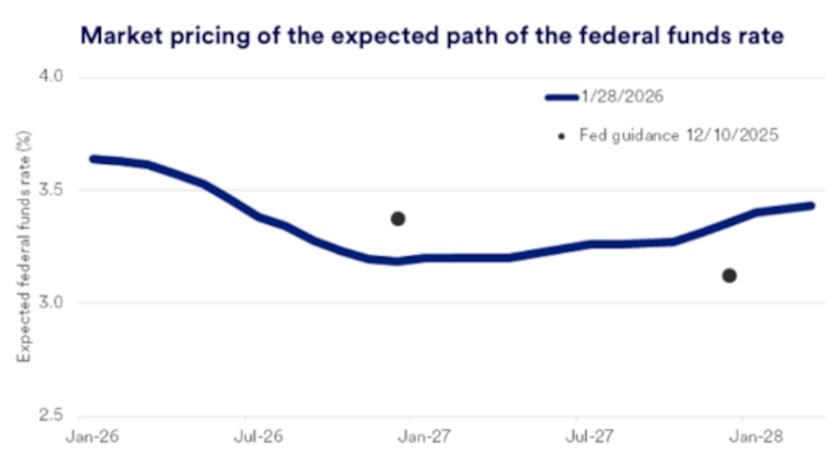

The Fed reduced interest rates at their last three meetings of 2025 to acknowledge softer labor market conditions even as inflation stayed elevated, and the Fed's projections show a mix of higher growth expectations in 2026 alongside lower inflation. 2 That mix aligns with broader market forecasts and an outlook for continued strong corporate earnings growth. When growth expectations stay firm while inflation expectations cool only gradually, longer-term yields can hold steady even as short-term yields fall.

“Economists predicted modestly higher inflation this year, and recent data confirmed those forecasts. Consensus now points to a gradual slowdown in inflation,” says Merz. “Tariff price pressures appeared in business surveys and accelerating core goods prices, but these effects haven’t been extreme.” Even so, inflation remains above the Fed’s target, and that persistence can shape both the pace of future rate cuts and how far longer-term yields can fall.

Policy decisions can pull yields in different directions, and bond investors often feel that tension most when the outlook changes quickly. At its January meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) kept the federal funds target rate at a range of 3.50 to 3.75%. Median Fed member projections anticipate one 2026 cut, 2 while investors expect two additional cuts, and that gap can create near-term bond market volatility. 3

Fiscal conditions also influence yields by changing the supply backdrop for Treasuries. “Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent does not plan to increase auction sizes for longer maturities,” says Merz. “Rather, the Treasury indicates it will issue more short-term bills, where heavy issuance is unlikely to disrupt broad bond market pricing in the near term.”

Congressional policy can add another layer because deficits and borrowing needs can increase Treasury issuance over time. The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” extends current tax rates, adds new tax cuts, and trims spending only modestly, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates could increase the federal debt by $3.4 trillion by 2034. Large tariff increases instituted in 2025 can partially offset additional spending if maintained in 2026 and beyond, but higher borrowing could still pressure yields if investors demand more compensation for growing U.S. Treasury bond supply and increasing fiscal uncertainty. 4

“Recently, rate cuts pulled Treasury yields lower,” notes Merz. “Over the long run, bond buyers want to see federal cash flow support bond principal and interest payments, which would suggest lower spending or higher taxes.” When investors worry that cash flows will not keep pace with borrowing, they may demand higher yields (and therefore lower prices) to compensate for those risks.

The yield curve, which compares Treasury yields across maturity dates, has moved closer to a more typical shape as these forces interact. Normally, longer-term bonds offer higher yields than shorter-term bonds to compensate investors for committing money for longer periods, but Fed policy can reshape the curve because it influences shorter maturities more directly. The curve inverted, meaning short term yields were higher than long term yields, from mid-2022 to later in 2024 as restrictive policy pushed short rates above long rates and markets anticipated eventual cuts.

Today, the 10-year Treasury yields 0.70% more than the 2-year Treasury, compared with an average spread of nearly 0.80% since 1977.1 Those shifts matter because they influence how much investors get paid to extend maturity and accept interest rate risk. Investors can use that “term premium” logic to decide whether to stay short, move to intermediate or long maturities based on how much additional yield the market offers for taking additional time risk.

Investors can still position bond portfolios to balance income, diversification, and risk management in this environment. A disciplined approach emphasizes diversification, avoids overconcentration in cash or very short-term instruments, and incorporates higher yielding bonds to enhance income while managing tariff-related inflation risk. Beyond bonds, global infrastructure and equities can also benefit from ongoing economic expansion, particularly if earnings growth remains supportive.

This environment rewards investors who treat fixed income as a toolkit rather than a single bet on rates. When investors spread exposures across maturity and sector – while respecting credit quality, liquidity needs, and time horizon – they can pursue yield without taking uncompensated risks. “Economic conditions can support continued earnings growth, creating favorable equity and real asset return opportunities,” says Merz, and investors can integrate that view with bond allocations that support portfolio resilience.

Talk to your wealth professional for more information about how to position your fixed income investments consistent with your goals, investment time horizon, risk tolerance and tax profile.

Investments in fixed income securities are subject to various risks, including changes in interest rates, credit quality, market valuations, liquidity, prepayments, early redemption, corporate events, tax ramifications and other factors. Investment in fixed income securities typically decrease in value when interest rates rise. This risk is usually greater for longer-term securities. Investments in lower-rated and non-rated securities present a greater risk of loss to principal and interest than higher-rated securities.

The municipal bond market is volatile and can be significantly affected by adverse tax, legislative or political changes and the financial condition of the issues of municipal securities. Interest rate increases can cause the price of a bond to decrease. Income on municipal bonds is generally free from federal taxes but may be subject to the federal alternative minimum tax (AMT), state and local taxes.

Bond yields respond to changes in the economy. When the economy grows quickly and inflation rises, bond yields increase. If the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds target rate, bond yields also climb. For example, when inflation surged in 2021, the Federal Reserve raised rates in early 2022, causing bond yields to rise. Conversely, when the economy slows or inflation stays low, bond yields drop or remain steady. In mid-2024, bond yields fell again after the Fed cut rates in September 2024, and longer-term yields have fluctuated since.

Interest rates directly affect bond prices. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall; when rates drop, bond prices rise. This relationship, known as interest rate risk, means that if you sell a bond before it matures, you may receive more or less than its face value depending on current rates. If you hold a bond to maturity, you typically receive its face value, provided the issuer doesn’t default.

You can find better return opportunities when bond yields are high. Higher yields generate more income and may reduce interest rate risk, since rates are less likely to rise much further. However, even when rates are low, bonds can still play an important role in a diversified portfolio. long

At its January policy meeting, the Federal Reserve held interest rates steady after three rate cuts in 2025.

We can partner with you to design an investment strategy that aligns with your goals and is able to weather all types of market cycles.