Weekly Economic Outlook

Data-driven insights from the week’s economic reports

Business-focused analysis from the U.S. Bank Economics Research Group

February 20, 2026

The week’s economy at a glance

Plenty of headlines, little resolution

This week’s economic narrative was dominated less by the data than by policy, as Friday’s Supreme Court ruling striking down tariffs imposed under emergency powers overshadowed an already busy slate of macro releases. While the decision materially alters the legal pathway for trade policy, it does little to change the broader economic outlook, as tariffs are likely to persist through alternative authorities and keep tariff‑related inflation in play. Against that backdrop, incoming data largely reinforced an economy that is cooling toward trend, rather than rolling over, with inflation progress remaining uneven and the Federal Reserve in wait‑and‑see mode.

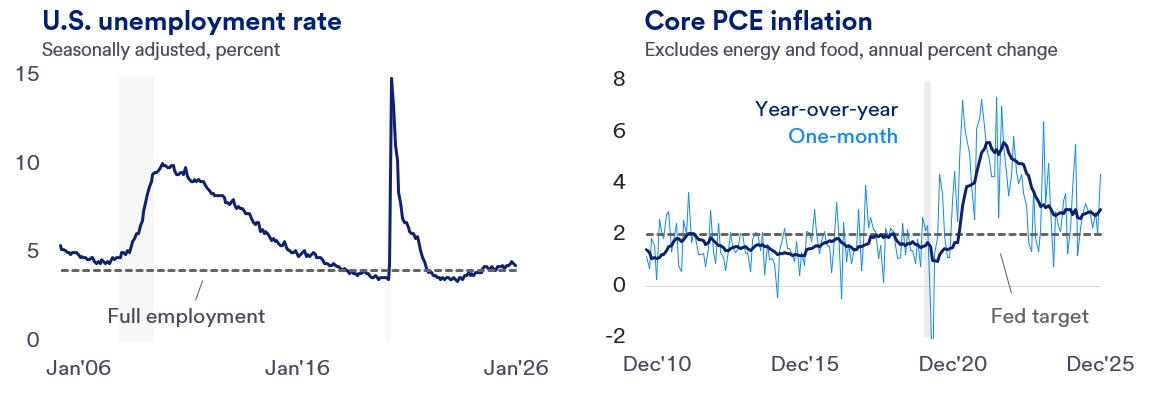

Core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) inflation firmed at the margin in December, rising to 3% year-over-year (YoY), reinforcing that disinflation remains bumpy rather than linear even as income growth holds steady and savings thin. At the same time, the advance estimate of fourth quarter GDP disappointed on the headline but was heavily distorted by shutdown effects, masking firmer underlying private demand. Housing data added further evidence of an economy adjusting rather than breaking down, with supply running ahead of household formation, sales volumes subdued, and pricing pressure shifting toward builder discounts rather than lower mortgage rates. Taken together, this week’s developments reinforce a patient, data‑dependent Fed, with policy easing still likely but contingent on clearer evidence that inflation is resuming a durable glide path toward target.

What this means for business: For businesses, the court ruling changes the legal mechanics of trade policy but not the operating environment, reinforcing the need to plan for continued tariff exposure, elevated input costs, and persistent policy uncertainty.

ECONOMIC DATA OF THE WEEK

3.0%

Core PCE inflation rose to 3.0% YoY in December, marking the highest reading since the first half of 2024 and underscoring the uneven nature of disinflation late last year. On a monthly basis, core prices increased a firm 0.4%, the fastest pace since February, lifting shorter‑run inflation trends as well, with three‑ and six‑month annualized core PCE both moving closer to 3%. The December pickup was broad‑based, reflecting a reacceleration in core goods prices – partly linked to tariff‑exposed categories and payback after earlier softness – as well as firmer core services inflation. Importantly, the distorting effects of the fall government shutdown appear to have had a more limited impact on PCE than on CPI (Consumer Price Index), leaving PCE inflation a cleaner signal of underlying price pressures at year‑end.

Meanwhile, outside of the price data, the Personal Income and Outlays report showed that income growth remained steady in December while the saving rate edged lower, reinforcing signs that household spending power is becoming more constrained as inflation progress stalls. Taken together, Friday’s PCE data are consistent with a Fed that remains on hold through the first half of 2026, awaiting clearer evidence that inflation is resuming a durable glide path toward its 2% target before easing policy later in the year.

ECONOMIC REPORT OF THE WEEK

Q4 GDP

Real GDP growth slowed sharply in the fourth quarter, rising at a 1.4% annualized rate – well below expectations (U.S. Bank: 2.8%; Consensus: 2.8%) and down materially from the 4.4% pace in Q3. However, the headline figure materially overstates the degree of underlying private sector cooling. The Q4 print was heavily distorted by the October–November federal government shutdown, which subtracted almost a full percentage point from growth, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Exports also declined, adding to the deceleration, while imports fell as well, providing a partial offset. Stripping out these volatile and policy‑driven components, real final sales to private domestic purchasers (a closely watched measure sometimes referred to as ‘core GDP’) rose a solid 2.4% annualized – slower than Q3, but still consistent with trend‑like growth and signaling that private demand remained intact despite a cooling labor market.

Under the hood, consumer spending continued to expand and remained the single largest contributor to growth, even as momentum moderated late in the year. Business investment was also a notable bright spot, accelerating in Q4 and driven in part by sustained strength in equipment and intellectual property – particularly tied to AI and data center buildouts. Residential investment, however, remained a drag amid high mortgage rates and price concerns. Taken together, the report reinforces a patient, data‑dependent Fed. Growth is clearly cooling from mid‑2025’s above‑trend pace, but the economy appears to be converging toward trend rather than rolling over, with shutdown‑related payback likely to lift measured activity modestly in early 2026.

CHIEF ECONOMIST QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“The Court’s ruling changes how trade policy is implemented, not the environment businesses are operating in. The practical reality is continued uncertainty, continued cost pressure, and little reason to plan for a quick return to a low‑tariff world.”

― Beth Ann Bovino, Chief Economist, U.S. Bank

Economic trends: International trade

Trade: Supreme Court strikes down tariffs imposed under emergency powers

On Friday morning, the Supreme Court ruled that President Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose broad‑based tariffs was unlawful, invalidating the legal foundation for most of the ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs announced in April 2025. While the decision creates uncertainty around whether importers will ultimately be refunded – potentially a one‑time fiscal cost exceeding $100 billion – the ruling is unlikely to materially alter the macroeconomic trajectory. Importantly, the Court’s decision constrains the process by which tariffs are imposed, not the administration’s broader trade posture. The White House retains multiple alternative authorities, including Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, to re‑impose tariffs on national security grounds, suggesting that headline protectionism is more likely to be reshuffled than reversed.

From a macro perspective, the ruling should not be interpreted as a meaningful disinflationary pivot. Businesses have already adjusted supply chains and pricing strategies around a higher‑tariff environment, and legal uncertainty has, if anything, delayed rather than prevented tariff pass‑through. Replacement tariffs are likely to be pursued under different statutory authorities, reinforcing the persistence of tariff‑related price pressures.

For the Fed, the decision does little to change the inflation outlook. As a result, the ruling reinforces – not relaxes – the case for a patient, data‑dependent Fed, with policy easing contingent on clearer evidence that inflation is sustainably converging back toward target.

Economic trends: Monetary policy

FOMC Minutes: Waiting for the 'all clear'

The January 27–28 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting minutes reinforced the core message from the decision. Policy remains firmly on hold after last year’s cumulative easing, with officials viewing the economy as expanding at a solid pace, the labor market showing signs of stabilization, inflation cooler but still above target. Against that backdrop, the Committee appears content to wait for clearer confirmation – either renewed disinflation or more decisive labor market softening – before resuming rate cuts.

The most notable element of the minutes was the discussion around communications and the symmetry of the reaction function. Several participants indicated they would have been comfortable acknowledging more explicitly that rate moves could go in either direction, including hikes if inflation remains above target. At the same time, several still judged that further cuts would likely be appropriate if inflation declines as expected, while others argued that additional easing should wait for clear evidence that disinflation is firmly back on track. The center of gravity still looks like ‘higher for longer,’ but not forever. Cuts remain the next likely move if inflation cooperates, though the bar for near‑term easing is materially higher than during the late‑2025 insurance phase.

On the macro outlook, the minutes emphasized a ‘low‑hire, low‑fire' labor market that may be stabilizing, with the vast majority judging that downside risks to employment have diminished. That assessment reduces the urgency for further near‑term easing, though some participants continued to flag nonlinear risks in a low turnover environment, where weaker hiring could still translate into a sharper rise in unemployment. On inflation, participants generally expect progress toward 2% as tariff‑related goods pressures fade and housing services disinflation continues, but many cautioned that the path could be slower and more uneven, leaving a meaningful risk of persistence. Stronger productivity, tied in part to technology and AI investment, was cited as a potential disinflationary tailwind, though not one that obviates the need for confirmation in the data.

The minutes also devoted attention to financial stability, with staff continuing to characterize vulnerabilities as notable. Officials highlighted elevated equity valuations, compressed credit spreads, and pockets of higher leverage within the financial sector, while flagging AI‑related concentration and opaque private market financing as areas to monitor. Overall, the message is of a Fed comfortable holding steady while it waits for clearer disinflation signals. The discussion of two‑sided risks adds a slightly more hawkish edge to communications, but does not materially change the likely direction of travel. We continue to expect 50 basis points of rate cuts in 2026, most plausibly beginning around mid‑year, as confidence builds that inflation is resuming a clear downward trajectory or if labor market conditions soften more decisively.

Economic trends: Housing sector

Housing: Plenty of homes, few buyers

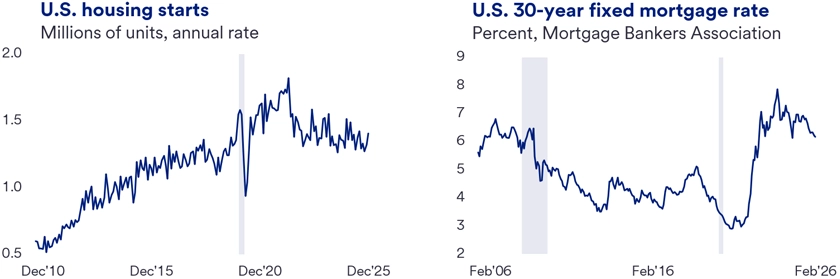

The housing market is increasingly a story of excess supply meeting constrained demand. New Census Bureau data show housing starts rose 6.2% month-over-month (MoM) in December, bringing total starts in 2025 to 1.36 million units. Despite marking the lowest annual total since 2019, construction activity remained well above the 2010–2019 average of roughly 1.0 million units per year. Importantly, this level of building is occurring amid a pronounced slowdown in household formation, reflecting weak affordability and one of the slowest periods of U.S. population growth outside the pandemic era. With a large volume of units already in the pipeline, housing completions are likely to outpace household formation in 2026 – a historically rare configuration that should place incremental downward pressure on home prices.

These supply dynamics are unfolding as the housing market is already experiencing subdued price appreciation, with most national home price measures showing low-single digit year-over-year gains, as both new and existing home sales remain historically depressed – constrained by weak affordability. Newly built homes have proven more price sensitive than existing homes, as builders are now sitting on the largest inventory of completed homes for sale in over 15 years. As a result, builders have increasingly turned to price concessions. Census data released Friday showed the median price of newly constructed homes was down 2.0% YoY through December. In fact, newly built homes were cheaper than existing homes for much of 2025 – another historical rarity – highlighting the degree of pricing pressure in the new home market.

While continued supply growth should help ease affordability constraints at the margin, prospective buyers should not expect a meaningful decline in mortgage rates from current levels. Mortgage rates are closely tied to the 10‑year Treasury yield, which has largely traded between 4.0% and 4.5% since late 2023. When mortgage rates peaked near 7.5% in late 2023, the spread between mortgage rates and the 10‑year yield was near historical highs, reflecting an inverted yield curve and elevated bond market volatility. As the yield curve and volatility have normalized, that spread has narrowed sharply and now sits only about 20 basis points above its 1990–2019 average. As a result, any further meaningful decline in mortgage rates would likely require a sustained drop in the 10‑year Treasury yield – a prospect that appears increasingly unlikely given fiscal sustainability concerns and ongoing heavy Treasury issuance.

Economic trends: The week ahead

Data and reports we’re watching this week: Inflation signals and labor market cross-checks

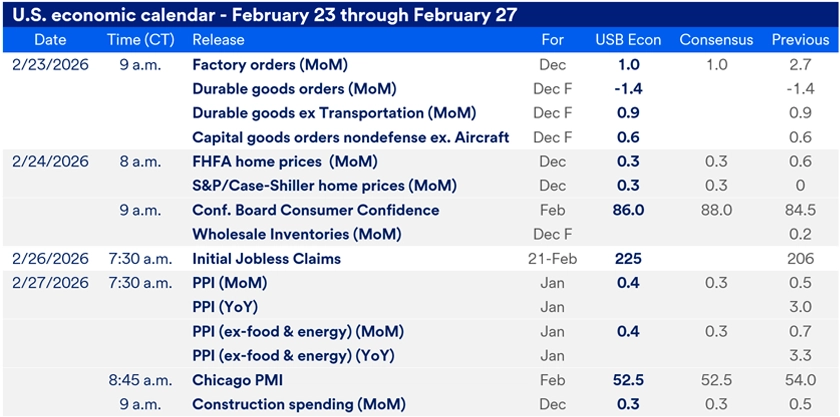

This week’s data calendar is lighter on top‑tier releases, with incoming reports likely to provide incremental color rather than a decisive signal on inflation or labor market conditions. With last week’s Q4 GDP estimate coming in softer than expected, distorted in part by shutdown‑related effects, and December PCE inflation running firm, markets will be watching closely for clues on underlying price pressures and labor market momentum.

Tuesday’s February Consumer Confidence report will offer an early read on household sentiment as the year gets underway. We expect a modest rebound following January’s sharp decline, though confidence levels are likely to remain depressed by historical standards. Persistent inflation pressures and only gradual cooling in labor market conditions continue to weigh on consumer perceptions.

On Thursday, Initial Jobless Claims should provide a timely cross‑check on labor market conditions. We expect claims to remain low and broadly stable, though with a modest uptick following last week’s unexpected decline. Overall, the data should continue to point to a labor market that is cooling gradually but remains far from showing signs of material distress, consistent with recent payroll and unemployment trends.

Friday’s January Producer Price Index (PPI) will be the key release of the week, as it provides critical insight into business input costs. We expect both headline and core PPI (excluding food and energy) to rise 0.4% MoM – somewhat firmer than consensus, but still representing moderation from December’s pace. January often brings seasonal price pressures, and several categories may again contribute, including airfares and health care services. Following a stronger‑than‑expected December print, the report will be closely scrutinized for evidence that upstream inflation pressures are either re‑accelerating or continuing to cool beneath the surface.

Finally, an active slate of Fed Speakers throughout the week may shed further light on policymakers’ interpretation of the recent data mix. Remarks from Governors Christopher Waller and Lisa Cook – both current voters – will be most closely watched, particularly for insight into how the Committee is balancing softer growth signals against still‑elevated inflation. Comments from Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee and Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic may also provide useful color on inflation dynamics and labor market conditions. With growth showing signs of moderation but inflation still running above target, any guidance around the balance of risks – and the timing of potential policy easing – will be closely scrutinized.

Economic data calendar this week

What we’re watching this week, including release dates and projections from the U.S. Bank Economics Research Group.

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) Speaker Calendar

- February 23, 7 a.m.: Waller (Board of Governors/Voter)

- February 24, 7 a.m.: Goolsbee (Chicago Fed/Non-Voter)

- February 24, 8 a.m.: Bostic (Atlanta Fed/Non-Voter)

- February 24, 8:10 a.m.: Waller (Board of Governors/Voter)

- February 24, 8:35 a.m.: Cook (Board of Governors/Voter)

- February 24, 2:15 p.m.: Barkin (Richmond Fed/Non-Voter)

- February 24, 2:15 p.m.: Collins (Boston Fed/Non-Voter)

- February 25, 9:40 a.m.: Barkin (Richmond Fed/Non-Voter)

- February 25, 12:20 p.m.: Musalem (St. Louis Fed/Non-Voter)

Next update: Week of March 2

For additional insights, see our Monthly Macroeconomic Outlook and Chief Economist Beth Ann Bovino’s latest commentary.

If you have any questions about any of the topics above or want to learn more, please contact us to connect with a U.S. Bank corporate and commercial banking expert.

Not currently a subscriber? Sign up to get our economic insights delivered to your inbox weekly.

Sources: U.S. Bank Economics, Bloomberg, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), U.S. Census Bureau, National Association of Realtors, Mortgage Bankers Association

Tags:

U.S. Bank Economics Research Group

Beth Ann Bovino

Chief Economist

Ana Luisa Araujo

Senior Economist

Matt Schoeppner

Senior Economist

Adam Check

Economist

Andrea Sorensen

Economist

Subscribe to our economic insights newsletter

Not currently a subscriber? Sign up to get our economic insights delivered to your inbox weekly.

Learn more

If you have any questions about any of these topics or want to learn more, please contact us to connect with a U.S. Bank Corporate and Commercial banking expert.