U.S. labor supply: From boom to bust

What is the most valuable resource in the world? Is it land? Trees? Oil? Minerals? Water? How about labor?

From factory and office workers to scientists in the lab, labor is the most important resource in the world. Human input is essential in the production of goods and services and is needed to discover and utilize natural resources.

This resource has been in sharp decline, largely from demographic changes. Since the post-World War II baby boom, labor supply growth has shrunk as the population ages and fewer babies are born. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts that without immigration, the population will begin to shrink by 2034.

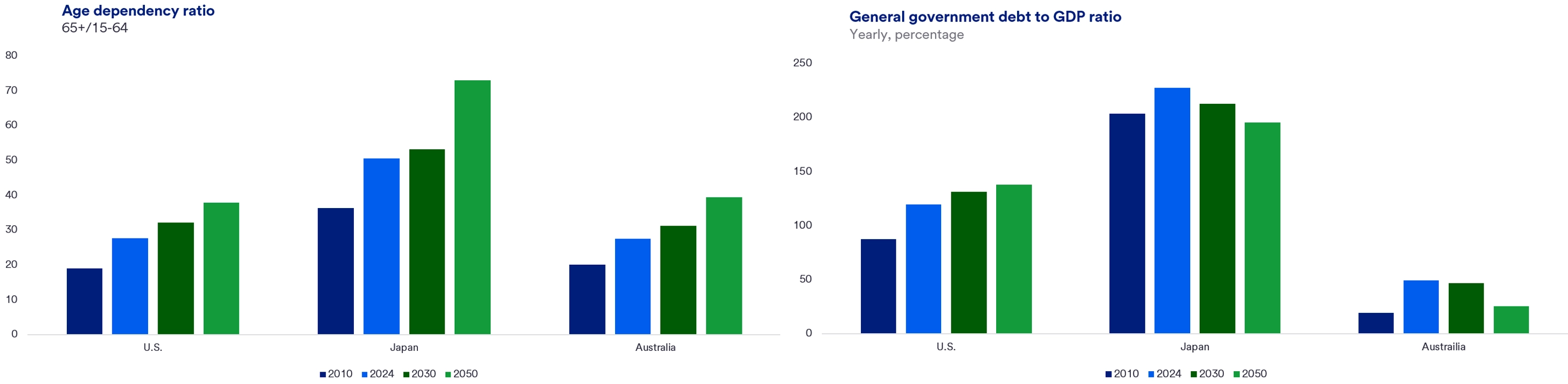

The pace of older people leaving the workforce is expected to continue over the next decades. The U.S. age dependency ratio, defined as the population age 65 and over as a share of the workforce, was 28% in 2024 from 19% in 2010 and is expected to reach 38% by 2050. Record breaking early retirements (age 55-64) further deplete the labor force. The U. S. economy loses their skill set and industry knowledge. The government loses their tax revenue to pay for retiree benefits.

There are not enough younger workers to replace these retired workers. The U.S. birth rate has been in fast decline, with the fertility rate now at 1.79 births per female, down from 3.65 in 1960. Since 1972, the U. S. birth rate has averaged 1.9, below the 2.1 birth replacement level needed to maintain a stable population without immigration. Net migration outflows last year further reduced labor supply, in fact Brookings estimates net migration outflows in 2025, for the first time in 50 years.

“A smaller population also means there are fewer people to spend on goods and services. Fewer households will be formed so fewer homes are bought. Lower buyer demand and higher production costs, if unchanged, will weaken U.S. businesses’ competitive standing in a global marketplace.”

Beth Ann Bovino, chief economist, U.S. Bank

There are some benefits for those workers still remaining. A shrinking labor force leads to a tighter labor market with higher wages as businesses compete for labor. A low unemployment rate and stronger household balance sheets will also improve borrower credit quality and are a plus for financial institutions.

But labor shortages also lead to higher business costs and larger skills gaps. This slows U.S. productivity and increases inflationary pressures. If businesses raise wages to attract candidates, these costs will eventually pass through to consumers. If the job can’t be filled, or is filled with unqualified workers, businesses lose efficiencies, reducing productivity and growth while adding to inflation.

A smaller population also means there are fewer people to spend on goods and services. Fewer households will be formed so fewer homes are bought. Lower buyer demand and higher production costs, if unchanged, will weaken U.S. businesses’ competitive standing in a global marketplace. With a smaller economy, there is less tax revenue to pay mandatory retirement pensions and healthcare benefits – already 46% of total federal spending – forcing the government to choose between higher taxes or higher deficits.

Potential solutions to the problem of a shrinking labor market require policy changes. First, there’s incentivizing and increasing automation and training to re-skill current and future workers. With the onset of AI, some of this is already happening organically, which has already improved productivity. But more re-skilling needs to be done to adapt to this changing workplace environment.

Second, to counter a declining native-born workforce, policy makers will need to adjust immigration policies to attract workers from abroad. While most European leaders and the U.S. have stood against immigration, the Spanish Prime Minister Sanchez has reportedly said that Spain’s choice is between “being an open and prosperous country or a closed and poor one.” Spain recently granted amnesty to 500,000 migrants. But net U.S. migration, according to Brookings, is now at its lowest rate in at least 50 years.

The U.S. is not alone in this problem. Other countries are aging with low birth rates. Japan and Australia also have an aging population and low birth rates. But Australia has an open immigration policy that has reduced its age dependency ratios, while Japan has tighter immigration policies, widening its age dependency ratio. Comparing economic conditions, Australia hasn’t had a recession in 25 years, while Japan slowly recovers from its “Lost Decade.” With Japan's government debt to GDP ratio over seven times larger than Australia, it seems that the former made the right decision.

Get more business-focused economic analysis

For additional insights, see our weekly economic report and monthly economic forecast.

If you have questions about any of the topics above or want to learn more, please contact us to connect with a U.S. Bank corporate and commercial banking expert.

Not currently a subscriber? Sign up to get our economic insights delivered to your inbox weekly.

Tags:

Explore more

Weekly economic highlights

Read the latest weekly update from the U.S. Bank Economics Research Group.

Monthly economic outlook

See the U.S. Bank Economics Research Group’s forecast for the upcoming month.

Past economic views

Visit the archive to read previous commentaries from U.S. Bank Chief Economist Beth Ann Bovino.